“…I knew I had not escaped Kentucky and had never really wanted to. I was still writing about it and had recognized that I would probably need to write about it for the rest of my life. Kentucky was my fate- not an altogether pleasant fate, though it had much that was pleasing in it, but one that I could not leave behind simply by going to another place, and that I therefore felt more and more obligated to meet directly and to understand. Perhaps even more important, I still had a deep love for the place I had been born in and liked the idea of going back to be part of it again. And that, too, I felt obligated to try to understand. Why should I love one place so much more than any other? What could be the meaning or use of such love?”

“I knew as well as Wolfe that there is a certain metaphorical sense in which you can’t go home again- that is, the past is lost to the extent that it cannot be lived in again. I knew perfectly well that I could not return home and be a child, or recover the secure pleasures of childhood. But I knew also that as the sentence was spoken to me it bore a self-dramatizing sentimentality that was absurd. Home- the place, the countryside- was still there, still pretty much as I left it, and there was no reason I could not go back to it if I wanted to.”

“But what I had in my mind that made the greatest difference was the knowledge of the few square miles in Kentucky that were mine by inheritance and by birth and by the intimacy the mind makes with the place it awakens in.”

“I came to see myself as growing out of the earth like the other native animals and plants. I saw my body and my daily motions as brief coherences and articulations of the energy of the place, which would fall back into it like leaves in the autumn.”

Wendell Berry[i]

My mother loves trees… and strawberry shakes.

I know this, because she tells me every Saturday. I pick her up at the ALF she lives in, and we go to Culver’s to get a small strawberry shake, a medium caramel shake for me (after all, I am bigger than she is…and growing bigger with each shake!). I used to also get onion rings, originally at her request, but the onion rings have stopped because she now refuses, or forgets, to put in her dentures, so they would be left for me to eat and I do not need them. Her absent dentures are a result of the fog of dementia which has deepened over the past 6 years through which I have lived near her. One reason I moved near her on the Central Gulf coast of Florida, was to help my sister and brother-in-law care for her. She is 94, and they have born the brunt of keeping watch over her slow deterioration. Dementia would be enough of a battle, but what makes the struggle worse, is my family’s life-long battle with her bi-polar disorder.

My brother, sister, and their spouses tell me I interact with mom the best of our family, which has been surprising to me considering how difficult our relationship was throughout my life. They also tell me that she says I am her favorite child. In the past, when they would say this, I would roll my eyes, and ask if they would like to trade me positions in the family hierarchy. They then assure me that neither of them will compete with me for the distinction. It is also surprising because with each visit, I never know who she will understand me to be.

Sometimes, I am her brother.

Sometimes, I am her father.

Sometimes, I am my father.

Sometimes, I am her boyfriend.

Sometimes, I am her son.

Sometimes, I am not sure she knows who I am, but there is a feeling of familiarity of someone she trusts. I like that. The trusting part, because it is so different and new.

After we receive our shakes through the drive-through, we go to a large park nearby. I drive slowly through the park, and she says…every time…that she loves the beautiful trees, which are a tangle of short palms, young oaks, and the occasional coastal pine. I usually point out the various shelters which protect picnic tables, and the gatherings of people underneath. Sometimes there are balloons and banners on the shelters which identify birthday parties or other gatherings. I mention them, because the gatherings warm my heart, and I hope the sight will warm her heart, too. Sometimes she will look at the gathering. Other times she can’t seem to tear her gaze away from the trees.

As we are approaching Culver’s, or the park, she will say, “This is where Larry brings me.”

I say, “Yep. That’s me.”

She will often respond, “Oh, yeah.” In her voice, I detect both embarrassment and humor, as if her mind still remembers how to be self-deprecating. I share in the humor with her. No reproach. “It is just how your brain works right now,” I tell her. She seems comforted by that sometimes.

One of the things she has recently repeated several times is, “You are my son, but also my brother.”

I like that…

It is profound…

…and it reminds me of how I feel about my own children. The thought describes both a genetic connection, but also a relationship on even ground, with none of the struggles for power that often characterize parent-child relationships. Unconditional, mutual love and respect, without attempts to manipulate the actions of each other.

So…

…a relationship completely different than the one she and I had throughout many of my 57 years with and away from her.

Now, her mental state often leaves her in a place before I was born. Before my brother and sister were born. Before she married my father, and all the years driving across the country from church service to church service. Back to when she was young. Either when she was a college student, or when she was a child. To be honest, her behavior is often that of a two-year-old. She can become so confused that her childhood memories invade the present. Not the memories themselves, but her view of the world then. The trees and plants around her ALF were planted by her father, she says. There is no reason to argue the point with her. No reason to try and pull her 85 years into the present. In those times, it is all she is capable of understanding. I think it is a way for her to survive the confusion. To make sense of not knowing or liking where she is. It may be comforting to be Home, if only in the deep recesses of her mind.

That is why she loves trees, I think.

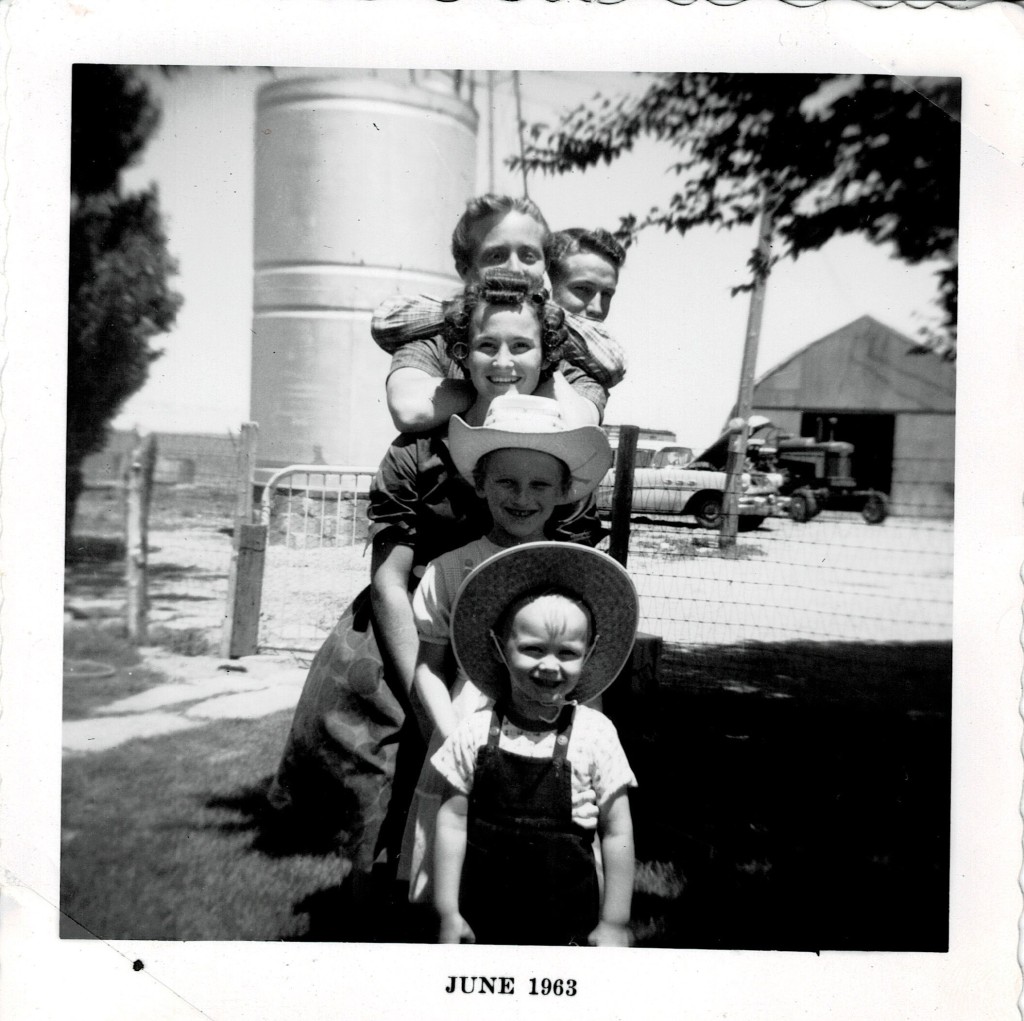

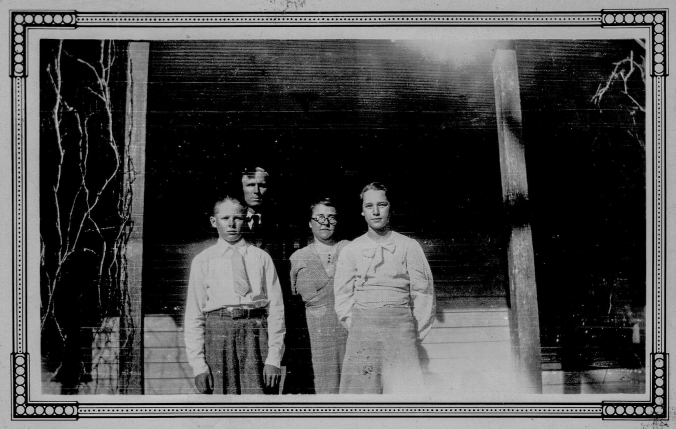

The place she is remembering, is School House Holler. I have been there once. It is in the hills of Southeastern Ohio, up-river from Huntington, WV, where she was born, and where her family moved when she was older. It is the place where her earliest memories lie. Her fondest childhood memories. Where her mother fed her cornbread and milk and flap-jacks and green beans with ham hocks and biscuits with milk-gravy. Where she worked with her brother pulling caterpillars off the tobacco plants and plopping them into a tin Hillsbrother’s coffee can with kerosene in it to kill them. Where she and her brother got sick when they rolled a tobacco leaf into a homemade stogie, hid and smoked it, then got a spanking when her mother found out. Where her daddy worked all week in an industrial job along the river, then came home to work all weekend in their large garden with multiple fruit trees and then hauled the garden harvest to the farmer’s market in town on Sunday to sell to city folks for extra money during the depression. Where her daddy had to park his pickup miles away when it rained and then walked home because the roads were too muddy. Where their single milk cow and mule and pigs were. Where her crazy grandfather lived with them and would frequently disappear and have to be searched for in the woods. Where all her sisters and brother walked down the same path, being joined by neighboring kids intermittently along the path to the one-room school in the valley. Where the house was small, but the country was big and beautiful and full of adventure.

THAT place!

Once, when I first moved here, she drew maps of the farm, and the layout of the kitchen, and showed them to me. I didn’t realize at the time the significance of the maps. I was still living with my own memories of her, I guess, so I was less receptive to her remembrances. I was amazed by her memory, then. Now I understand it was her attempt to go Home again. Just like her love of the trees in the park every Saturday.

She was born fourth among six children, three years younger than her brother, Harold, and three years older than her sister, Betty. She seems to have been closest to Harold, although it may just seem that way, because the stories she told me about School House Holler usually include him. The two of them either busy working or getting into minor mischief together. There were always chores to do. The house had neither running water, nor an indoor bathroom, so there was always water to fetch, a cow to milk, or eggs to gather from the chicken coop. It was at School House Holler that her work ethic was born and honed.

I think her bi-polar disorder also contributed to her need to be up and moving. Even now, when she falls into a nap in some chair, unexpectedly she will awaken and begin to immediately get up, which is not as easy a task as it was even one year ago. When I am with her and she does this, I ask, “Where are you going?” Her response to me is a blank stare, then maybe, “Connie is coming…” or some imagined task. I will say, “No…it’s ok. There is no reason for you to have to get up.” It seems to be the way her brain works. It does not stop, as if there is a perpetual thumb in her back pushing her to go and do. She obsesses about things. When she was younger it was religion and reading the bible, to herself, or to whomever was nearby. At the ALF, she added working in the yard, planting and trans-planting plants, pulling weeds, or wanted plants masquerading as weeds in her mind.

These two activities often got her into trouble in her ALF.

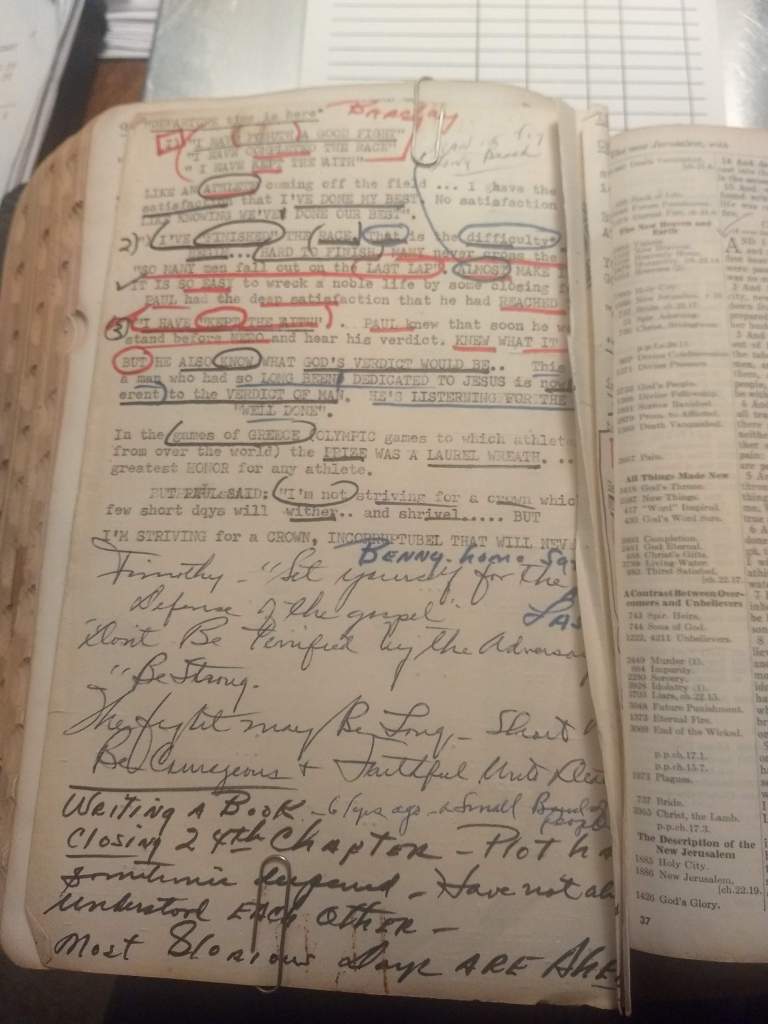

Meal time bible reading…

Often, at meal time, when everyone in the facility was in the dining room, she would take her bible (one of five she has) and begin to read aloud…really loud. She either could not understand that everyone didn’t want to hear Leviticus at meal time, or she did not care if they wanted to hear it. “They need to know Jesus!” she would exclaim, and it did not matter that they either already knew Jesus, knew about Jesus, or that there was nothing in Leviticus ABOUT Jesus. THEY NEED TO KNOW! Eventually, I began to think the bible readings were less about Jesus and either more about her need to be seen and heard or that she perceived God to demand it.

In years past, I would have said that Mom loved God above trees or strawberry milk shakes. Now…I’m not so sure…

When I consider my mother’s relationship to God currently, I must be honest that I do NOT know what disjointed thoughts go through my mother’s mind, nor can I trace the lines of difference between who she was and who she now is. First, because we didn’t know about bi-polar disorder when we were growing up, so all we knew of Mom was how she acted, and what she said. Second, because I must overcome my own inner issues with who I knew her to be, and the way I interpreted her thoughts and feelings towards me as a child, adolescent, and man. Third, because my expectations of her have not been met.

Now, her actions regarding God seem to go between two spiritual poles:

Jesus, lover of her soul…

Or

God, demander of perfection…

Both these perceptions seem to be held within a brain that is rapidly deteriorating, so there is no logic holding them together. Instead, she flips between the two when she relates to other people. She is sweet as French Silk pie until she gets angry, then she is mean as a rattle snake. She does not like to be bossed, especially by women, and she can be quick to strike out with her fists when someone is directly confronting her in an action she is taking, no matter how dangerous or non-sensical the action. The part of her brain within which civility was constructed is broken and has given way to the part of her brain that runs the survival program.

I often wonder if Mom retreats to School House Holler because it was a time before there was a dissonance in her perception of God. While I have learned that the memories of childhood are clearer for a person disappearing into the fog of dementia than more recent ones, possibly due to where they are stored within the brain; I also wonder if the complexity of theological messages she received through the years are harder for her to integrate. It is also possible that she never did integrate them. I have come to understand that throughout her life, Mom did not think critically about differing interpretations in the theology with which she came in contact. Once she heard something she understood as true, she held on. I think she believed theological doctrines for reasons even she wasn’t aware. This is a facet of her personality directly attributed to bi-polar disorder. When she latches on to a thought, she is like a pit bull holding on to a log. Even though pit bulls to not eat logs, and it makes no sense to hold on, it seems to be the principle of the thing: “You WILL NOT take this log from me! It is mine, and I want it!”

She can be stubborn like that.

Although I am not completely clear on this, I don’t believe she encountered church and an orderly, theological belief system until after her family moved from School House Holler. I believe they moved to a house along the river when she was in junior high. She came to faith at a revival meeting in a small, very conservative church when she was 15 or 16. She must have been quite popular with the elders of the church, because they offered to pay for her tuition in God’s Bible School, a religious boarding school in Cincinnati, Ohio, approximately 150 miles from home. Mom accepted the offer, leaving home to attend GBS 150 miles away at 16.

From what I have learned, God’s Bible School was known for two things: a legalistic, conservative theology and evangelistic fervor. If it was like what I saw in the tradition when I was a child, there was a strict dress code. Especially for women. They always had to wear dresses with hemlines below the knees, and sleeves stretching below the elbow. (I guess I never realized how sexy elbows and knees are…) There was to be no make-up worn or jewelry of any kind, including wedding rings. The women also could not cut their hair, nor wear it down. It had to be piled up on top of their head or wound into a tight bun which seems to have been preferred. Interaction between men and women would have been limited to classes, church, and evangelistic activities. Evangelism was a strong priority, defined as telling other people about Jesus, and warning them that they were headed to hell after they died if they didn’t believe certain things and then adhere to a strict life-style which emphasized self-denial and obedience to the church hierarchy. The organized evangelistic activities included teams of people that would stand on street corners, sing, and proclaim the gospel of Jesus through bible reading, preaching, giving out tracts, and talking with people. Mom was an enthusiastic participant in street corner evangelism, even to the point of going by herself when necessary. It is from these experiences that her ALF, meal-time bible reading comes. It’s how she was raised to be and do in her earliest experiences with God, minus the dress code….

Yard work…

I moved to Florida in January of 2012. My son helped me, and we took our time on the trip, spending the night in Memphis. We listened to the blues on Beal Street, toured Sun Studio, and visited the Lorraine Motel, site of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and now remade into a civil rights museum. Our arrival in St. Petersburg was sometime in the early morning hours. Later that morning, after a late breakfast of biscuits and gravy…my favorite… made by my sister, Connie, the three of us went to see Mom at her ALF. Connie asked Mom to take us on a tour of the grounds. While we walked, Connie explained to us how many of the plants we saw had been planted by Mom. Baird and I were amazed by the number of them, and how much work it must have taken by my then 88-year-old mother. During the tour, I don’t remember my mother saying very much, unless it was to explain the plans she had yet to complete. Although I might have described my mother at the time as being active, I didn’t realize just how physically strong she has been and still is. Within the past year, that strength has considerably lessened, and she needs a walker to help her keep from falling, but that strength is still there, especially when she gets mad.

Eventually, gardening became an issue. Mom would constantly be outside working in the yard, even in the heat of the Florida summer. She would be so focused on what she was doing, she would forget to drink or eat. Sometimes, she would pull up plants that were part of the landscape plan, and either try to transplant them, or throw them away. While pulling at a small tree root, she would lose her grip and fall, sometimes hitting her head, and nobody would know about it until she came inside with a black eye or bruise. Her clothes were often dirty. She always had cuts on her legs. But she would not stop! It became a problem…

Despite many warnings, she persisted. Even when the owner locked away her tools and put a lock on the water faucet. She would make do with other objects as tools and put a container under the AC condensation spout for water. Once, before they locked the water faucet, she attached the hose, and walked in front of the smokers on the porch with the water on full to water the plants. One of the smokers…a woman…confronted her, kindly reminding her she wasn’t supposed to use the hose and telling her she was spattering water all over the smokers. Mom turned the hose on her. In the resulting struggle for the hose, the faucet was damaged so that water was spraying from it. The water had to be shut off, and the faucet fixed. Everyone said it was Mom’s fault. She wasn’t popular for awhile after that incident. (When I heard the story, I was extremely doubtful that she had the strength to break that faucet. That was four years ago. Now, I think it at least possible…)

One good thing about her yard work was that she would at least sleep through the night. Or, at least until 4:30-5 in the morning. She would then get up and begin the day by reading her bible, which could often be a problem if she had a roommate. It is a behavior of which I am both profoundly aware and to which I shake my head with feelings of embarrassment and dark humor. She COULD have gone into the dining room with her bible, and allowed her roomie to sleep, but…no. It is an action that can be defined as one of devotion to God, but also as passively aggressive. Everyone SHOULD be up reading their bible at 5 in the morning, right?

As my mother’s physical ability has diminished, the issues with her working in the yard have ended. Instead, her brain continues to push her to do…something…she just doesn’t know what that something is. Two Christmases ago, I gave her a large pack of colored pencils and several adult coloring books. I chose books that had floral arrangements bordering scripture passages or historic prayers. My hope was that she would become obsessed with them instead of working in the yard. I also thought they would allow her to still express her creativity, and then she would have art she could hang on her walls or give away to family and friends. It worked. For about a year and a half. She would sit for extended periods of time meticulously coloring those pages. She especially loved the book filled with prayers.

I am not surprised she loves the prayer book. Prayer has always been important to her. She has spent countless hours through the years praying for her kids. She will then tell us about it, too. In years past, she would sometimes call and eventually ask, “Is everything ok with you? I woke up last night and the Lord brought you to my mind, so I prayed for you.” Nice story, right? God and my mother have my back, right? Well, sometimes it was. Other times…

My mother was seriously aggressive and judgmental and controlling and discouraging…passively. She would often send letters which explained “what she was learning in scripture…” It soon became apparent that what she was “learning” was what she thought I should know or do. If she were to be asked why she would write such letters, I am sure her eventual answer would be that God wanted her to. They were “The Epistles of Helen.” I didn’t realize it at the time, but what I took from these letters, what they communicated to me, was that there was always something wrong with me. I wasn’t good enough. It did not matter that I had a strong spiritual life and was struggling to unearth much needed grace from a theological belief system that I was increasingly finding inadequate to explain a loving God. It did not matter that I was trying to live in and by that unearthed grace, all the while being distracted by money issues, raising children and living in a difficult marriage. It also did not matter that I was an intelligent adult.

She still had to write…

Or send me books…

Or send cassette tapes…

Or call me…

I found out later, that my former wife eventually would open the letter before I got home, and when she found the letter to be unhelpful, she would throw it away. I appreciate that. After our divorce, I would do the same. I would read the first lines, and when I saw the tone headed in a particular direction, it would go into the trash. To some, this practice might sound harsh, or even rebellious. And it was rebellious. But it was a rebellion that was necessary. It was born out of a need for self-protection and a process of redefining myself, and God. It is never a good idea to try to form your understanding of Self and God from the template built by a mentally ill mind.

What I find interesting, though, is that Mom doesn’t seem to carry that destructive, ungracious morality when she is centered in the world of her memories of School House Holler. When she is Home, all is orderly, and in balance.

For her sake, I wish she could have lived in that place longer…

For my sake, I wish I had a similar place…

[i]The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry; Paul Kingsnorth; Counterpoint; Berkley, CA; 2017; Pg. 6,7,8.